All over the world, Don Quixote is regarded as a masterpiece of world literature, admired for its many literary qualities. But its true meaning is often misunderstood. Let’s now explore why that is—and why the time has come to finally make it public.

The Birth of the Novel

Cervantes follows the path laid out by the literary genre known as the picaresque, the origin of what has become today’s predominant literary form: the novel. The picaresque is sometimes referred to as “literature of the poor” because its characters are neither princes nor seekers of glory—they’re simply trying to survive. Yet the picaresque is, in fact, a theory of knowledge that properly begins with La Celestina (1499), which is still written in dialogic form—a hybrid of novel and drama, an attempt to search for truth through the shared human experience rather than through abstractions or imagined ideals (ideas).

This phenomenon is specific to Spain, most likely as a result of the coexistence of the three monotheistic religions, or Religions of the Book, until the 15th century. This unique context had already given rise to a particularly realistic literary tradition, as seen in the comparison between The Poem of the Cid and other European epic poems. The renowned philologist Menéndez Pidal even described it as a “psychological” epic. Realism intensified and turned inward for reflection with the official imposition of Christianity throughout Spain. After La Celestina came Lazarillo de Tormes in 1554 and Guzmán de Alfarache in 1599. The first part of Don Quixote was published in 1604.

Although the picaresque accurately portrays the gap between imagined ideals or ideologies and the reality of life, it also—perhaps unconsciously and paradoxically—adopts a postulate of idealism: that the root of evil lies in human nature, in the passions that control us, especially greed and lust. As a result, the brilliant Guzmán de Alfarache is terribly pessimistic, concluding that we should expect nothing from this life and can only find consolation in the next.

Cervantes shares the realistic style and inquisitive drive of the picaresque but disagrees with its conclusion. In Don Quixote, the only preliminary poem signed by the author himself refers to Lazarillo and La Celestina; the rest are written by fictional characters who humorously address their counterparts in Don Quixote. In the prologue to the second part, Cervantes points out that his novel is exemplary, as opposed to the scandalous nature of those that came before. This becomes especially clear in the interpolated tale The Curious Impertinent, which has nothing to do with the main story of the knight, but instead deals with two virtuous adulterers who fall to temptation due to an irresistible circumstance—one that could have been avoided if not provoked. I encourage readers to explore this story and they will easily understand its message. (1)

Evil Is the Weapon

For Cervantes—as for any person—evil is the intent or will to cause harm. Cervantes’ merit lies in revealing and explaining how the weapon, which contains this harmful intent, operates through its mere potential—and therefore through its very existence, which predates humanity and to which we have had no choice but to adapt.

Our problem is that, since we don’t recognize malicious intent, we also don’t seek to eliminate it. It’s not really a matter of free will—it comes upon us. Even worse, we use imagined ideals to differentiate ourselves as humans and to justify harm, forcing others to confess and believe in them by projecting harm through the weapon. That is how people align themselves with our weapon against others’.

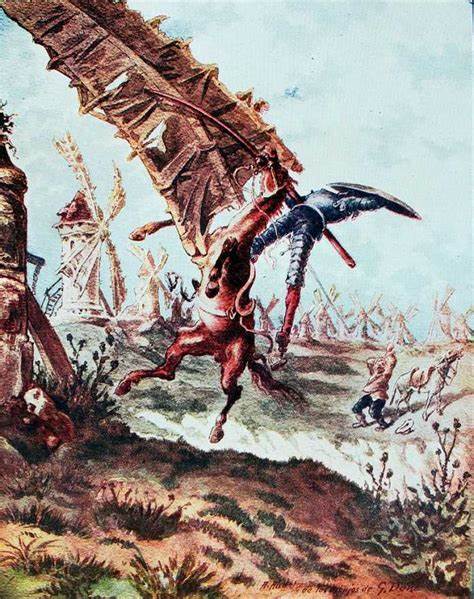

That’s why those who encounter Don Quixote—like the girls at the inn or the innkeeper—fear him just by seeing his weapons, even though he has no offensive intent. They act and confess as he wishes, follow his language, his rituals, his nonsense, and chivalric madness without much issue, because words and actions can adapt to anything; we are all capable of imagining anything. The same will later be done by Juan Haldudo. Until Don Quixote meets the Toledo merchants, who are strong enough to stand up to him—they mock him, and ultimately beat him.

Don Quixote arms himself and ventures into the world to make people confess (to Dulcinea’s beauty), but this madman’s quest is, in fact, a depiction of real life, which is faithfully revealed throughout the novel—especially in the tale of the captive and the real-life references to renegades, or in the case of Zoraida, who raises suspicion because she hasn’t yet been baptized, etc.… And in this way, the novel explains the meaning of all ideologies and imagined systems in the world, from ancient religions to modern democratic politics.

The Reception of Don Quixote

Cervantes’ contemporaries not only welcomed Don Quixote with enthusiasm and delight—they also understood it perfectly. Cervantes did not conceal his purpose; in fact, he provided a very clear key to ensure there would be no doubt about what he was addressing. This was clearly recognized by Dámaso Alonso, the great 20th-century philologist and poet, who served as president of the Royal Spanish Academy in the 1950s. Alonso wrote several works on Don Quixote, including El hidalgo Camilote y el hidalgo don Quijote (“The Gentleman Camilote and the Gentleman Don Quixote”) (2), in which he demonstrates that the origin and reference point for Don Quixote is the character Camilote, from the second book of Palmerín de Oliva (1516), better known as Primaleón—a very popular book in its day, with numerous editions.

In Primaleón, Palmerín is already Emperor of Constantinople when Camilote arrives with his unattractive fiancée, Maimonda. Camilote asks to be knighted so that he may defend her honor and, more than that, force the knights of the court to confess through combat that she is the most beautiful woman in the world. After killing several knights, he is eventually defeated and slain by Don Duardos. Furthermore, The Tragicomedy of Don Duardos by Gil Vicente—the most famous Portuguese playwright of that time (and arguably of all time)—focuses entirely on this story and presents it in a comedic tone, much like Don Quixote. Dámaso Alonso even published a Spanish edition of Gil Vicente’s Don Duardos. There is no doubt Cervantes was familiar with the work, especially given his deep interest in theatre and the fact that he spent time in Lisbon. Alonso identifies seven parallels between Camilote and Don Quixote and concludes that it is impossible for Camilote not to be Cervantes’ reference—so evident, in fact, that had it not been intentional, Cervantes would have had to take deliberate steps to prevent readers from drawing the inevitable connection.

Thus, the novel’s meaning was clear upon its release and caused great distress to Lope de Vega, the leading intellectual of his time. Lope declared and threatened: “no poet is foolish enough to praise Don Quixote,” because Don Quixote unmasks power—it reveals the projection of the weapon—and strips it bare, leaving no room for ideological disguises. This is likely why Lope—or someone in his circle—authored the spurious Don Quixote. The mysterious author Avellaneda was probably a pseudonym for Lope, known as the “Phoenix of Wits,” whom Góngora mockingly referred to as “Llano” (Flat) instead of Vega (Meadow) in his poem Patos del aguachirle castellana, to highlight his superficiality. The prologue to the false Quixote is filled with resentment toward Cervantes, whom it belittles and even mocks for his missing hand. It also alludes to the “voluntary synonym,” which is undoubtedly Camilote. The false Don Quixote concludes with the madman being taken in by the charitable care of the Nuncio of Toledo.

Don Quixote then fell into obscurity in Spain and was only rediscovered in the 19th century—precisely when the poor Spaniards learned that it was highly valued in other European countries (see Don Quixote in the Land of Faust by Bertrand). But by then, its interpretation—when not deliberately and furiously suppressed by those who perceived its true meaning and were themselves ideological leaders like Lope—was subject to distortion or outright nonsense. Our modern world is almost entirely idealistic or figurative, and realistic experience has been forgotten. Dámaso Alonso himself pointed out that what we call “realist novels” of the 19th century are not truly realist, since the characters do not respond to their circumstances—they are crafted as ideological tools of the author. He referred to this as “literature of the particular.” In light of this situation, a few words here about the meaning of realistic thought may be worthwhile.

Literary Realism

Western thought is Platonic, based on ideas, or Aristotelian, based on syllogisms. In contrast, realistic thought is based on analogy or comparison, using our ability to place ourselves in another’s position. It appeals to lived experience and, as such, gives rise in the West to the genre of the novel. In China—lacking Greek-style abstraction and myth—classical philosophy expresses realistic thought through present or historical cases. These serve to let each person virtually experience the protagonist’s situation and decision and draw their own conclusions—primarily to judge whether it is exemplary or not. Note, for example, how The Analects of Confucius begin:

Chapter 1

1.1

“The Master said: ‘Is it not a joy to learn something and then to apply it at the right time? Is it not a pleasure to have friends come from afar? Is it not the mark of a gentleman not to be upset when his merits go unrecognized?’

Beyond the practical aspect of learning—knowledge is power—we are encouraged to see learning as a joy, likened to welcoming a friend who comes from a distant land, someone we treat with interest, respect, and care after a long journey. We expect them to share news and customs from outside our world, giving us the chance to compare our circumstances with theirs. Similarly, by studying, we come to understand authors from centuries past, gaining self-confidence and proof of our intelligence. We no longer need others to judge or validate us—we already know our worth. This brings composure, dignity, and satisfaction.

The Western syllogism, unlike analogy, is typically ideological or totalitarian: it begins with a universal premise and derives a particular one. All men are mortal; Socrates is a man; therefore, Socrates is mortal. The issue is that in everyday life, syllogisms often hide one of their premises (Aristotle called this an enthymeme), usually the universal one, which remains implicit—and that’s what gets “confessed.” For example: Manuel Herranz is Spanish, therefore he is dumb (hidden universal: All Spaniards are dumb).

In La novela cervantina, Dámaso Alonso defines literary realism as “the enlivening by which words raise the very argument to life.” He notes that Cervantes goes a step further than all prior realists—he moves from the “realism of souls” to the “realism of things.” For what determines human behavior is the weapon and its projection of threat. Cervantes states this quite plainly in Don Quixote at various points: “It is the same to say arms or war” (Chapter XXXVII. Speech on Arms and Letters) and Cervantes repeatedly points out that the true problem of evil is not the grievance (agravio)—which can be forgiven, repaired, or settled through compensation or justice—but the affront (afrenta), which sustains the offense and forces the other into a situation where the only options are submission, flight, or confrontation. There is no room for reconciliation or remedy. That is precisely the situation caused on us by weapons, whose mere existence projects harm.

Indeed, in everyday life we apply a basic form of realism—economic realism—since it’s easy to recognize that any ideological narrative benefits the one who funds it. But that is a blind perspective, one that cannot explain how, simultaneously, it leads to (mutual) self-destruction. Cervantes also suggests that justice (distributive—which causes inequality) originates from the arm. While Sancho follows his master partly for wages, he mainly accompanies Don Quixote in hopes of winning an island, the Insula—for material goods are the spoils of the weapon, to the extent that they serve it.

State totalitarianism does not deny or prohibit economic realism—just as the exchange of goods between states (weapons) requires an acceptable international currency or intermediaries, such as the historical role played by the Jews. Though their relationships as armed units are a zero-sum game, such arrangements are tolerable as cooperation against third parties—just as the U.S. and China once allied economically against the Soviet Union. That alliance no longer makes sense now, hence the current shifts seen in Trump-era policies. What the state cannot allow is for its ideologies—its figurations—to be questioned, because doing so would challenge the state itself and undermine its function: war.

The White Flag

The truth is that Cervantes—unlike what institutional intellectuals like Lope might believe—does leave us with choices. He shows us that human beings are equal and, thus, different and independent from the weapon. He proves this by showing that we can distinguish ourselves from it through the white flag. The white flag appears in Don Quixote at a crucial moment: during the encounter between the captive and Zoraida (3), it serves to enable the love between two people of irreconcilable faiths—faiths that, in their time, divide and bleed the world. And Don Quixote raises that white cloth atop the royal and colorful flags cart after he emerges unscathed from his encounter with the lion.

In our world, we all tend to reject or look down on the white flag, as it halts the weapon—evil itself—for the weapon, surrender is its meaning. But Cervantes does not use the white flag to signal surrender, nor does it have that effect in either case. Through this, he shows us the distinction between human beings, who have diverse choices, and the weapon, which has only one: to inflict harm. In doing so, he reminds us—and strengthens in us—the hope and certainty that we can overcome evil.

The wisest and best thing is for the kind reader to read Don Quixote, or at least try the opening chapters of the first outing, which likely correspond to the original exemplary novel that sparked this great adventure and vast creative development, once Cervantes realized the truth and power of his thesis. And don’t skip the Prologue—written likely at the end of Part One—where one can sense the author’s satisfaction, fully aware of the unique and transcendental significance of his work.

(1) At the same time as Don Quixote, two interesting short picaresque novels were published: La Pícara Justina and El Guitón Honofre. However, after Cervantes, who explores the picaresque genre further with two of his Novelas Ejemplares, Rinconete y Cortadillo and El Coloquio de los Perros, offering intriguing perspectives, the picaresque genre will no longer have significant relevance as a theory of knowledge. It will remain merely as a style—practically a pose, as can be clearly seen, for example, in El Buscón by Quevedo or in the delinquent novels of Salas Barbadillo. It should be noted, however, that there is one extraordinary exception in the last of the genre, quite late in 1646, Estebanillo González, a man of good humor, a rogue who navigates between the two factions of the Thirty Years’ War, disdainful of both its violence and its motives (figurations or ideologies), and is solely focused on his business, tricks, and surviving as best as he can.

(2) Alonso, Dámaso (1933): “El hidalgo Camilote y el hidalgo don Quijote,” Revista de Filología Española, no. 20, Madrid. Dámaso Alonso (1958): Del siglo de oro a este siglo de siglas. Madrid, Editorial Gredos (second edition in 1968). It also includes “Sancho-Quijote; Sancho-Sancho” and “Una maraña de hilos,” a study related to the Cervantine play Los baños de Argel.

(3) The same captive’s adventure is explored by Cervantes in a play: Los tratos de Argel, where the white cloth is repeatedly shown to the audience through windows on the stage.